|

THE BOY WHO NEVER GREW OLD

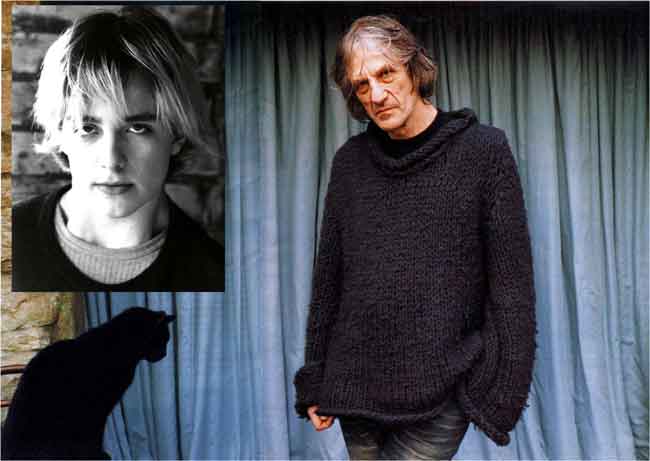

As an authority on JM Barrie, Andrew Birkin wanted his

son to grow up a poet like the real-life inspiration for

Peter Pan. When Anno Birkin blossomed into an exceptional

creative force, his father's wishes were granted - until

tragedy struck in a cruel echo of the past. By Jessamy Calkin.

Photograph of Andrew Birkin and Thomas the cat by Gautier

DeBlonde. Photograph of Anno by his mother, Bee Gilbert,

in April 1998.

|

In

February of this year, a little club called West One

Four in West London hosted an unusual event: the posthumous

launch of a CD by a band called Kicks Joy Darkness.

The evening was also a tribute to a 20 year old musician

and writer called Anno Birkin, who died in a car crash

with two other members of his band on the freeway

outside Milan in November 2001. As the evening unfolds,

some of his extraordinary poems, both visceral and

delicate, are read in fits and starts by friends,

family and admirers, including Hayley Mills, the writer

Bruce Robinson, and actor Ian Holm. There is some

live footage of the band and a video projection of

Anno's aunt, the singer Jane Birkin, reading one of

his poems. About 100 people are there, including his

brothers David and Ned, and some of his cousins, and

the actress Milla Jovovich, one of Anno's greatest

loves. The event has been organised by his mother,

photographer and writer/producer Bee Gilbert, and

his father, Andrew Birkin. Tall and thin, handsome

in a ghoulish way, Birkin is waving his arms around,

directing operations, dancing like a wayward spider.

Film maker, writer, anarchist, alchemist, archivist

and intellectual, Andrew Birkin is an obsessive man

whose life has been redefined by the death of his

son. He's an eccentric and talented man, a film maker

of high repute and low profile, a sought after script

writer, and the world's foremost expert on J M Barrie

and Peter Pan. He is probably best known for

his film The Cement Garden, and most recently

he has been adapting the book Perfume for the

producer Bernd Eichinger. But for the last 18 months

his world has been taken over by something else: creating

a monument to his son, Anno: collating all the music

and words he ever wrote, every photo of Anno, putting

out a CD and getting his poems published. This total

immersion is typical of Birkin - when he wrote a script

about Napoleon he read 88 books in six months; more

than just an expression of grief, he says, it is a

way of coming to know his son, of researching every

facet of his short life, of creating a new form of

biography.

*

* * |

|

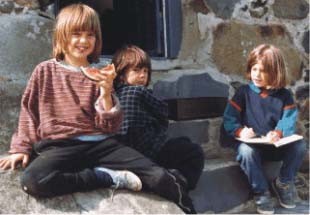

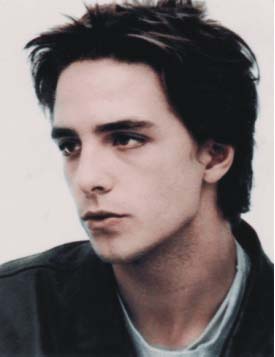

Anno

in 2000, photographed by his cousin

Kate Barry |

|

|

Anno

was born in London on December 9, 1980, on Andrew's

birthday, which was also the day that John Lennon died.

("When I arrived at the hospital and saw all the

long faces, I though Bee must have had a miscarriage,"

says Andrew laconically.) When Anno was two, the family

moved to Wales, to an old abandoned farmhouse on the

Lleyn peninsula, a place so remote that at night there

were no other specks of light visible anywhere on the

horizon. It was never meant to be a permanent home,

says Andrew, who has always thought of himself as having

no fixed abode, but nonetheless he has lived there ever

since, although Bee (from whom he has now separated)

lives in London. The farmhouse – in a glorious

place, looking out over fields and hills, there is a

stream and horses, a wood – is like a gothic museum.

A native Welshman called Ken has been doing it up for

nearly 20 years now.

|

Around the main house is a collection of outbuildings,

containing Andrew's laboratory, his wine cellar, a recording

studio, an art room. There is Ned's toy museum, the

children's library, which resides in a gallery above

the chapel/cinema - a screening room with a lectern

above ("I

raided a church for the furniture") - and some original

photos of J M Barrie and the Llewelyn Davies brothers who

were the inspiration for Peter Pan. It was here that

Andrew showed Anno the film The Bicycle Thief when

he was 17, and was moved when Anno, who'd been so quiet

throughout that Andrew thought he'd fallen asleep, burst

into tears and ran up the nearby mountain. It was the same

mountain from which Andrew fired Anno's ashes into the sky

in a rocket, three years later. Next to the screening room

is Andrew's library, which houses his 8,000 books, one wall

of which is dedicated to Napoleon. In another building,

through a trapdoor and down some stone steps, lies the wine

cellar which, as well as bottles of 1808 Madiera, 1914 Yquem

and 1945 Lafite, contains the ephemera of bottles previously

drunk - little bunches of petrified grapes, and their corresponding

corks, the seals from the bottles. It is, says Andrew, the

closest he's ever come to keeping a diary. In an outbuilding

next to the cellar is his laboratory, built when his son

Ned dropped out of school due to dyslexia and Andrew decided

to teach him chemistry, physics and biology. It is a beautiful

place, a laboratory out of Gormenghast; stone floors

and wooden shelving on which perch a stuffed fox, bottled

specimens (a lobster in a jar bears the words "Do Not

Eat - Ned"), and the walls are lined with a myriad

of glass bottles and jars - Hydrogen, Sodium, Neon, Argon,

Krypton, Gallium. It is like poetry. There is Niobium, Zirconium,

Germanium, bunsen burners and petri dishes in which Andrew

knocks up a few impressive experiments, an alchemist in

his lair, extolling the virtues of certain properties with

real love in his voice. Plastic models of clusters of molecules

hang from the ceiling - "That's Vitamin B12, that's

ecstasy..." says Andrew, pointing to them. He loves

chemistry. When he met his girlfriend Karen a couple of

years ago, the clincher for him was not her remarkable beauty

but the fact that she had done chemistry A-level. Opposite

the cellar is Anno's original recording studio which has

been turned into the HQ for the Anno archive, and it has

become the beating heart of Andrew's life. Here, for the

last 14 months, he has been cataloguing his son's work -

collecting, sorting, sifting, transferring, transcribing.

All Anno's poems - or his words as he used to call them

– his songs, everything he ever recorded. Thousands

of photos of Anno since he was a baby, all scanned onto

computer. Film and video of him throughout his life; box

files of his schoolbooks line the shelves (Holland Park:

French and Mathematics, Malibu High: English), files labelled

"To be Sorted" and one called "Everything

Else". CDs, cassettes, DATs, computers, photos of Anno

on the walls: Anno with blonde hair, dark hair, long hair,

short hair. Anno in a mask, in a hat. A magazine picture

of Milla Jovovich with Anno's handwriting scrawled across

it: "In my heart she will burn like a lie for life

/ Like a scar, she's for life..."

| What

is he going to do with this meticulous archive of

his son's lost life? He is releasing the CD, and is

publishing a selection of Anno's poems,

but there is clearly more to it than that. He rolls

a cigarette thoughtfully, it is as skinny as he is.

"Given the fact that I can't put the clock back,

I've learnt so much from him, and by going through

all his poetry, all his thoughts, he's taught me as

much - if not more - than I ever taught him."

Later I hear something similar from Ian Warwick, Anno's

English teacher who became his mentor and friend, and who now teaches the teachers of gifted children.

"I learned easily as much from Anno as I taught

him," he says, "and I can't think of another

student of whom that is the case." Birkin's friends

are united in thinking that it's something he's got

to do - after all, it's not out of character. We are

talking about a dedicated and solitary man. It's just

the way he is. When he was 20 and all his friends

were out partying, he went and camped out on Lundy

Island for three months and wrote a script of Jude

the Obscure, living on Pro Plus and Weetabix.

"Whatever gets you through the night," says

Bruce Robinson, his friend of thirty years. "That's

how he's getting through his night. Andrew's a very

obsessive man; he's either obsessing about mathematics

or Napoleon and now he's obsessing about his dead

son. And that's a place I can't go with him. I adored

Anno, I've known him since he was born and I've seen

him grow up. Andrew's coped with his death as a project,

he's coped with it in a creative way even though what

he's done doesn't immediately strike you as a work

of art; he's used what he knows - his creative ability

and his research skills - to survive. I can well imagine

that most |

|

|

|

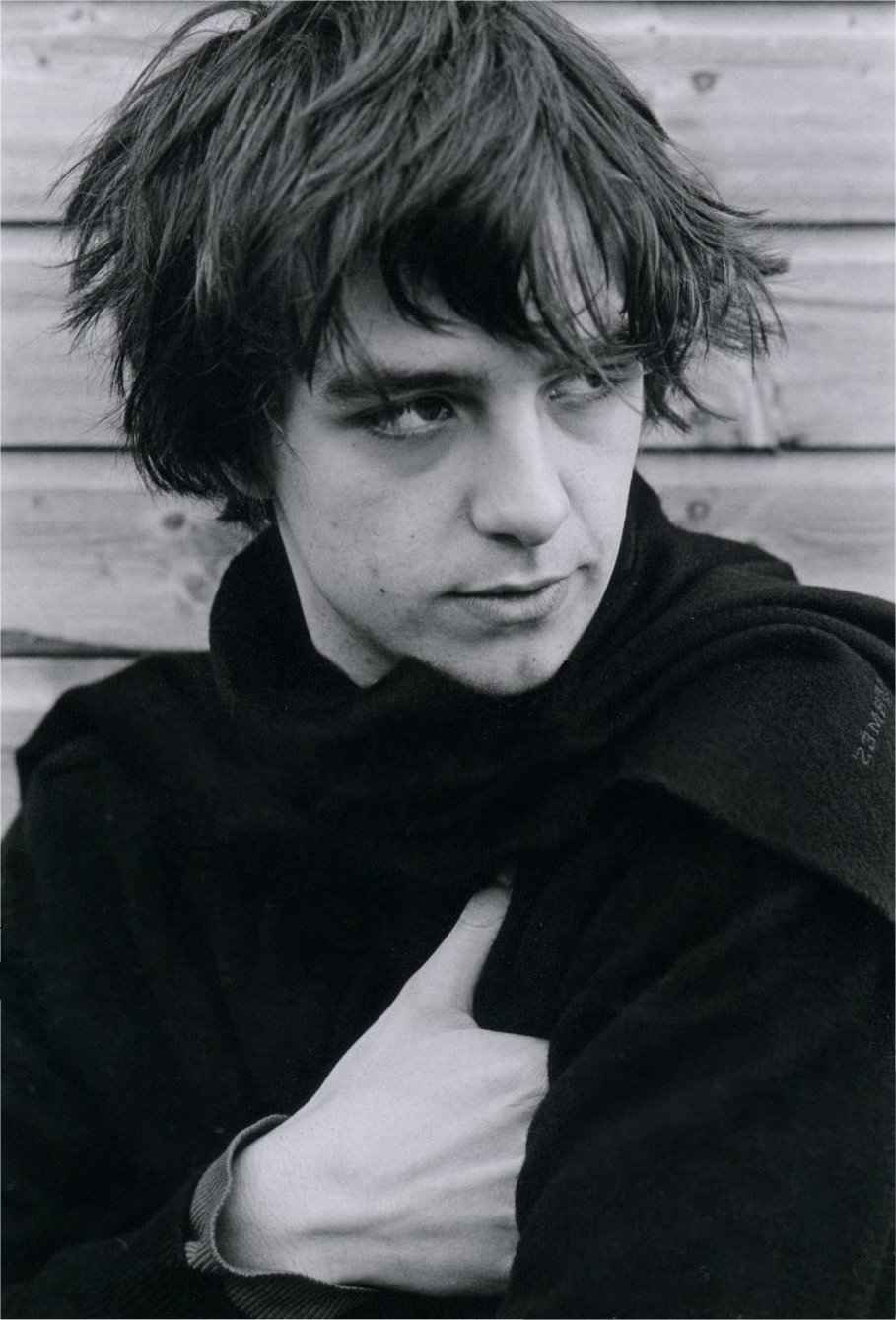

Top:

Anno Birkin with his mother, Bee Gilbert, in 1982.

Above: Anno, aged 7, at the farmhouse in

Wales with his brother Ned, 3, and cousin Lou

Doillon. |

|

people,

myself included, would have been too devastated to do anything

constructive, but out of the tragedy he has made ... well,

there's no gravestone for Anno, but there's an enormous memorial,

isn't there?"

* * *

Andrew

Birkin likes to talk, and he often takes a long time to

get to the point, though he gets to it in the end, usually

via a dissertation which might involve a mad mathematician

called Kurt Gödel and his Incompleteness Theorem, Heisenberg's

Uncertainty Principle, Michael Faraday's maths, non-maths,

irrational numbers and degrees of infinity. Napoleon is

likely to come into the conversation more often than not,

and he may well touch on quantum mechanics, non-locality

and dark energy. Sooner or later he'll get round to answering

the question. But whatever we talk about, the conversation

invariably comes back to rest on Anno. When we talk about

the finality of death for example, Birkin says: "When

it comes to this kind of phenomena - and I have to be careful

here not to sound like I know a lot about science, because

I don't, I just skim the surface - but everything I've come

across in quantum mechanics leads me to suppose that life

and death is simply one way of looking at something, and

that there is another way which is non-reducable, which

cannot be articulated mathematically. And when it comes

to life and death (and there are those, of whom I was formerly

one - an atheist - who would put themselves very squarely

in the set of knowing that death is the end) the reality

is that we cannot possibly know. Cardinal Newman wrote that

death is a horizon, and what is a horizon but the limit

of our sight?" "He's an exceptional man,"

says Bruce Robinson. "I find him utterly fascinating,

yet exasperating - one of the most exciting blokes

I've ever met - he's all of those things. I am one of the

few people who can say 'Shut up, who gives a fuck about

Schroedinger's fucking theory.' We laugh about it. He knows

I'm always on his side."

|

| Andrew's

laboratory, which he built for his son Ned's science

lessons after Ned dropped out of school. Photo:

Gautier DeBlonde |

|

|

Birkin

was born in 1945, the son of actress Judy Campbell and

ex-SOE member David Birkin, and brought up on a farm

on the Wiltshire/Berkshire border with his younger sisters

Jane and Linda. "The interesting thing about the

Birkins," says his schoolfriend, the actor Simon

Williams, "is that all their brilliance and eccentricity

seems to stem from an incredibly tight family unit,

and however they arrived at being who they are, it all

comes from the fact that they absolutely adore each

other." Jane Birkin remembers their childhood as

an idyllic time. "I don't think we ever got over

it," she says. They were all three at boarding

school but the holidays were "miraculous. We had

our fun like savages; we'd get on our bikes at dawn

and be gone for the day. We had an eccentric and wild

childhood which was what I tried to recreate for my

own daughters. If Andrew could find an abandoned house

we |

were in

it. I was very lucky to have such an adventurous brother because

I was always rather safe - he was the chief and Linda and

I were his lieutenants, standing guard and whistling should

anyone come along." Andrew went to Harrow where he didn't

deliberately set out to break rules, he was just oblivious

to them. Williams remembers him as "the most exhilarating

person I've ever known. He was dangerous, funny - he was just

better than most people. I remember being in the sanatorium

with him, sitting there on our antibiotics taking turns to

play the Paul Scofield part in A Man for All Seasons.

He knew all the dialogue." When Winston Churchill was

due to make an appearance at the school and cancelled because

he had a temperature, Birkin sold the story of his illness

to the Evening Standard in order to buy his first film camera.

His father was appalled at such behaviour and persuaded him

to give the money to charity - then bought him the camera

anyway. "We made a little film which was really designed

to accommodate my attraction to his sister Jane and his attraction

to my sister Polly," says Williams, "but it was

just an excuse to do a lot of running about and snogging really.

I think there still exists about 20 minutes of completely

superfluous footage of me and Jane kissing on Battersea Park

boating lake which Andrew then very sweetly agreed to re-shoot."

Andrew is only a year older than Jane, and Bruce Robinson

thinks of them as the masculine/feminine versions of each

other. "They have a real beauty about them. Well, Andrew

looks like something the cat brought in now - he's the worst

dressed man in England - but when he was young he was very

handsome. He has an astonishing sense of self, but no vanity

about that self." Birkin's first job was in the mail

room in 20th Century Fox, and his first major revelation was

working on Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Kubrick was his mentor, who took a delight in educating him

cinematically. As a teenager, Birkin was never obsessed with

sex, he was obsessed with love. "I was profoundly in

love, from the age of 15 to 21, with the same girl [Hayley

Mills], who wisely left me for an older man. By that stage

I was working on 2001 and my love for her became a

great love for cinema." Sitting in the Kalahari desert

he wrote his first film script. Birkin has always been a nocturnal

creature with an appetite for the darker classics: Huysmans,

Maldoror, Tarkovsky. Bruce Robinson used to nickname him The

Embalmer, because of his general demeanour and habit of getting

up with the setting sun. "When I first met him he had

somehow purloined a whole section of his sister's three-tiered

wedding cake and he lived off wedding cake, coffee and cigarettes.

And he sometimes used to turn up with a live sheep in his

car. It was his pet, it lived in the car and came out and

fucked about then went back in there..."

In 1968

Birkin worked on Kubrick's aborted Napoleon (which

spawned his lasting adoration of Napoleon; 20 years later

he wrote his own script which got shelved after Gerard Depardieu

made his own version for French TV. It sank without trace

and Andrew is confident that his own will re-surface). In

the 70s he wrote screenplays for

David Puttnam, including Inside the Third Reich which

he spent two years researching

|

with Albert Speer. For various reasons, this film never

saw the light of day, and Birkin's next big project

was The Lost Boys, an exquisite and beautifully

written five hour trilogy for the BBC, telling the story

of J M Barrie and the five Llewelyn Davies boys who

were the inspiration for Peter Pan. Birkin had

first become intrigued by Barrie when he had the job

of co-adapting the story for an American musical. Mia

Farrow was playing Peter and Birkin fell in love with

her and made himself into a Barrie expert in order "to

stay in her orbit". He developed this into an outline

for The Lost Boys and then his researcher tracked

down the last survivng Llewelyn Davies brother, Nico,

with whom Birkin exchanged 600 letters, and he discovered

a wealth of material. The film, which became a book

– J M Barrie & the Lost Boys –

starred Ian Holm as Barrie, and Holm's partner Bee Gilbert

subsequently became Andrew's for 20 years and the mother

of Anno and Ned. Birkin continued to write screenplays

and made a brilliant short film, Sredni Vashtar,

which won the BAFTA award and got an Oscar nomination,

wrote and directed The Burning Secret, and wrote

the screenplay for The Name of the Rose. He is

probably best known for his 1992 project The Cement

Garden, from the book by Ian McEwan, which won him

Best Director at the 1993 Berlin Film Festival. It was

the last film he directed. He has always said he would

prefer the company of an intelligent child to directing

Faye Dunaway, any day, and he just wanted to be with

his children in Wales. And in the same way that Barrie

dedicated his life playing with the Llewllyn Davies

boys, |

|

|

| Andrew

(cast as a monk) and Anno in 1984, during the

making of The Name of the Rose |

|

photographing

them, recording what they said in notebooks, so too did Birkin

with his children and their cousins and friends. Ned and Anno

mostly grew up in Wales, sometimes joined by their half brother

David (Andrew's oldest son by a previous relationship) and

it was there too that all their cousins would often congregate

in the holidays - Jane's three daughters Kate, Charlotte and

Lou, and Linda's three sons George, Henry and Jack. Much of

Ken's work back then was to build tree houses and other contraptions

for the children. And in the middle of it all would be Andrew

playing with them, madly. When he was seven, Anno wrote a

poem:

My Papa

is so tall and thin

He dos not have a dubble chin

His hear is black and getting grey

He dose not see a lot of day

he sits and rits all through the night

and dose not like the site of lite.

He likes to play like a child

And really is very wild

We have adventures all the time

I'm really very glad he's mine.

|

| Anno

and Ned with one of Ned's lizards (1990) |

|

|

It

must have been something, growing up in this magical

place, with a father like that. "If there is such

a thing as reincarnation, I'd like to come back as one

of Andrew Birkin's children," says Simon Williams.

Jane warmly remembers summers in Wales with everyone

racing around in the middle of the night on wild adventures,

led by Andrew, having mud fights, water fights, playing

Manhunt, which involved being chased through the woods

- Andrew still plays that at 57. Bruce Robinson marvels

at Birkin's rapport with children. "He's a sophisticated

intellect, and always has been, but at the same time

he can make gear shifts that I can't make, wherein he

can be perfectly comfortable with kids at their level

of functioning and do what they do - you know, rushing

off to the woods with flashlights, whereas I'd rather

be sitting in front of the fire with a bottle of red."

In Andrew's films of Anno playing with his cousins,

there is always Bee's voice in the background, intoning:

"That's enough now," and then "Be careful

now..." And then, "Stop before someone gets

hurt!" "You can often hear her saying that,"

says Andrew, smiling. "While I would just carry

on filming." Bee was the voice of reason, the one

with the blankets and the hot bath after the midnight

games. Andrew was more reckless. It is hard to separate

the real Anno from his father's vision of him, but talking

to anyone who knew him you can hear their voices break

under the weight of their anguish at losing him. "He

was like light," says Jane simply, "in that

if he came anywhere near you, you felt better. He had

very wide arms that he used to hug you with, and everyone

remembers his hugs, and everyone remembers that he always

had time for them. |

And his

time was very precious, but we didn't know exactly how precious."

"I have both your madnesses inside me," Anno wrote

in Close to the River, of his parents. "I am in

constant disagreement with myself ..." This is the poem

that Jane is currently reading on her world tour, Arabesque.

"He seems to have conjured up in just a few words what

every adolescent feels," she says, "and how most

of us have forgotten what that feeling's like. I don't think

I'm being over sentimental. I think he had something very

great in him." It is true that his poems have a wonderful

type of rhythm and an evocative resonance which is very sophisticated

for a boy of his age:

She

drew me my dreams, and with ease she unrumpled

a mind convoluted and crumpled

that was mine then but now is for none save the one

who shall someday receive me completely.

So with eyes to the floor I stand, sorry and sore,

and I long for that sleep to defeat me,

so the whole world may breathe me as you did so easily,

silent in moments of knowing. ... Anno

was 18 when he wrote that. Andrew had heard his music

and read lots of his lyrics, but it wasn't until after

Anno's death that his words emerged in notebooks and

on scraps of paper, everywhere. "He was exceptional,"

says Ian Warwick, who now works with gifted children.

"He was always two steps ahead, and he was way

wiser than his years. As a writer myself, I used to

look at his words and think, My God, I wish I could

write like this." "He was a serious talent,"

agrees Bruce Robinson, "there's no question about

it - there was a proper poet emerging there, if not

already emerged. His poetry is very sophisticated

and it has tremendous signature. He was the sweetest

man. And he's gone." |

|

|

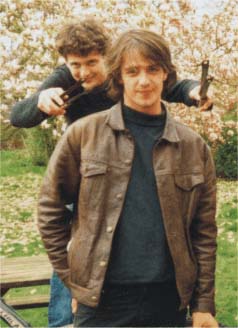

| Anno

in 1996, aged 15, with his English teacher Ian

Warwick (left) |

|

* * *

Andrew

had always hoped that one of his sons would be a poet. In

his introduction to the new Yale edition of J M Barrie

& The Lost Boys, he writes: "My son Anno was

born on my birthday in 1980. As he and his brothers grew up,

I came to experience first hand the joys that Barrie had so

longed for - "my boys". I secretly wished that one

of them would be a Michael - the poet among the five Davies

brothers - but as a boy, Anno seemed much more like George,

with lashings of Nico's humour. Then, around his 15th birthday,

a sort of miracle occurred, and Anno suddenly blossomed into

a poet and musician of great originality."

The figure of Michael has become almost totemic in Birkin's

life. Barrie had been besotted with the entire Llewelyn Davies

family, and when the boys' parents died he adopted them and

paid for their education, but Michael had always been his

favourite. In May 1921, Michael, by this time at Oxford, went

bathing in the river Thames and drowned. He was one month

short of his 21st birthday. Barrie heard the news from a reporter,

and was thrown into a slough of despair from which he would

never completely emerge. "What happened was in a way

the end of me," he wrote to Michael's tutor, "and

practically anything may be forgiven me now." Michael's

death had a profound effect on everyone who knew him. "I

am sure if he had lived he would have been one of the remarkable

people of his generation," wrote Lytton Strachey to Ottoline

Morrell. "The uselessness of things is hideous and intolerable."

Michael was buried in Hampstead cemetry. Eighty years later,

Andrew went there to find his grave. That day was the last

that he saw Anno alive. Anno went off to Amsterdam with his

brother Ned, then to Venice with Milla, and then to Milan

with his band to record their first album. Hours before his

death, Andrew spoke to him on the phone for a long time, and

was struck by how happy he sounded. At the end of the conversation,

Anno said: "We'll see what the morrow brings," which

had been Andrew's father's last words before he died nine

years ago. Anno and the rest of the band – Alberto, Lee

and Billy – went out to dinner, where Anno sat writing

a poem on a napkin, which he then - oddly - entrusted to Billy,

who had decided not to to accompany them to the club they

were going on to because

he had a headache. They were driving in thick fog on the autostrada

outside Milan.

|

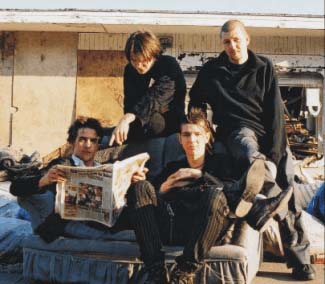

| Kicks

Joy Darkness in July 2001. L to R: Anno, Billy,

Lee and Alberto |

|

|

Alberto - completely sober - was at the wheel and Anno

was asleep in the back with Lee, when their car went

into the back of a lorry which had earlier been involved

in another accident. No one had cleared the first car

off the road, and in swerving to avoid it, their car

hit the lorry. Anno, Lee, Alberto and a friend, Giorgio,

were killed instantly. Anno was one month short of his

21st birthday. The driver of the car who caused the

original accident had fallen asleep, Andrew later learned,

and is now being prosecuted by the Italian authorities.

Andrew has posted the following message on the KicksJoyDarkness

website: "As Anno's dad I have no real interest

in who was at fault ... the man who fell asleep has

the

rest of his life to live. So if anyone in Italy knows

the driver involved, be so kind as to pass on this message:

it could so easily have been me at the wheel, and your

son on the back seat." |

Andrew had just returned from a camping trip to Scotland (he

had been to the island of Eilean Shona, where Barrie had spent

his last summer with Michael in 1920) when Alberto's mother

called him with the news. When Andrew phoned Bee in London,

she cried "Not Anno, Not Anno ..." because she was

always more worried about Anno than the others. He went straight

to her flat in Iverna Court, and shortly afterwards to Italy

with his sons David and Ned, and they went to visit Anno in

the mortuary and saw that he'd cut all his hair off, shaved

it to the bone before he died. They had some time alone with

him and Andrew had Anno's hands cast in plaster by the man

who cast Toscanini's hands – and he has them now, in

his sitting room in Wales, in a little shrine. Andrew had

brought some of Bee's hair to put next to Anno's skin, under

his shirt, in the coffin, and they also put in his front door

keys, a penny (for the ferryman - and a pound in case the

price had gone up) and a very big joint. (When Andrew opened

the ashes later - and it was no easy task, you're not allowed

to scatter ashes in Italy, so the box was lead-lined and doubly

sealed - he found the penny still there, everything else gone.)

Bee remained in London. "She couldn't have come,"

says Andrew. "She made it through in a different way.

There was a constant stream of people at Iverna Court, it

was open house: Bee's friends, Anno's friends, all being very

supportive. Bee was ... perfect, but she's different from

me, in some ways enviably so. I would like to be the sort

of person who needed to just close my eyes and feel the hands

in the darkness; as it was, I was the one with the tin opener

having to open the lead-lined box ..." He brought the

ashes back to London and later Billy came back, bringing with

him Anno's precious notebooks and his guitar. "That was

the thing that completely broke me and Bee up," says

Andrew. "Not the ashes, the guitar. Anno had travelled

everywhere with that guitar. That was the howl of grief."

"I never, ever again want to see anything as terrible,

as sad, as his parents at that time," says Jane. "They

were so generous with Anno - flinging open their house, his

recording studio, his words, his ashes, his everything - to

his friends and cousins. Andrew and Bee have been so impeccable,

you feel they are doing it the way Anno would like it."

Jane no longer calls Anno her nephew. "I call him my

brother's son, so as not to ever, ever pull his light or his

glory onto me. He was theirs, he was theirs. And the sadness

is theirs."

Ten days after Anno's death, Andrew returned to Wales along

with about 80 people - Anno's half brother Barnaby Holm from

LA, his half sister Lissy, his friends and cousins, his Milla

and his Honeysuckle - the two girls he had loved most at various

times – and Ken built a huge bonfire and they let off

20 huge rockets, the biggest you can get. Then Andrew took

the nose-cone off the 21st rocket and put in a great wad of

Anno's ashes and fired it from the top of the little mountain.

"It was a cloudy evening except for a patch of sky that

suddenly cleared to reveal a single star, and the rocket took

off in the direction of this one star, and suddenly it burst

over the Irish sea - it was extraordinary. And we could hear

a great wave of sound coming up the mountain -- a huge cheer

from all the people round the bonfire." Anno's ashes

have now been scattered all over the world by his family and

friends.

|

| Anno

and his brother David in April 2001, photographed

by their grandmother, Judy Birkin |

|

|

They

have been thrown from a coral reef in the Indian Ocean,

off the coast of Kenya, into the Pacific, the Nile,

off Kiwayu. They are under a chestnut tree in France

and by a stream in the Luxulyan Valley in Cornwall,

and they grow through the roots of a silver birch tree

that Bee planted for him in her garden. "By his

side," she writes tenderly on the memorial page

of the KjD website, "is a maple tree for dear Alberto

and a prickly holly for the prodigal Lee..." Later,

a year after his death, she has added: "365 days

and not one when I didn't think of you, my darling Anno."

Not long after the rocket ceremony was Andrew's birthday

– December 9 – which would also have been

Anno's 21st, and there was another gathering of friends

and family in London, and Andrew opened a jeroboam of

1982 Beychevelle. "To say that it was wonderful

is the wrong adjective. I don't think there is an adjective

that describes that occasion in one word ..." he

says now. Shortly after that he was anxious to start

"rescuing Anno's stuff." He and Ken retrieved

hundreds of bits of paper and notebooks and cassettes

from Wales and London and collected them all together

and Andrew's work had begun. He spent months collating

the music and the words, putting stuff onto the website

with Nao, one of Anno's friends, selecting and transferring |

music

onto CD,

copyrighting everything, choosing poetry with Ian to anthologise

into a book. There were 57 recorded songs, 20 hours of mini

discs, over 1,200 poems and lyrics. The cataloguing alone

ran to 1,000 pages. It is, he says, the most concentrated

work he's ever done ("except possibly Napoleon, which

was the training for it"). For

a year he didn't see a film or watch TV. "It was every

waking hour, and I was on the telephone a lot - to Ned and

David, Bee, Milla - but because I was surrounded by all the

material up here, I didn't feel the loss, the separation,

perhaps as greatly as they did, because they immediately had

to get on with their own lives." Jane asked, "Do

you miss him?" and Andrew said, "He's with me all

the time, he's on my shoulder." An entry on the KJD website

from Andrew reads: "At 4 am this morning I transcribed

the last of Anno's words from the vast amount he left behind.

I was dreading the moment, and secretly hoping it might have

some special significance." This

is what he found:

|

My whole life hangs tonight – like water –

swelling to the final drip.

My grip on nature fumbles – as I

stumble backwards – over rhetoric & rhyme.

The rumble in my heart could uproot heaven,

and all their ghostly judgement is like air –

is naught at all.

The dust that is my body shall be

one dust once – again –

with all things, not soon... not soon enough –

Ring the bells of murder –

Jesus sleeps –– in every one of you.

Wake!

Wake sweet prince & sing!

Fill

the avenues – with laughter.

Scream your words of

goodness in my ear –

let me hear – what I have done.

I seek just closeness with my fellow man.

|

|

| Anno

in 2001: a passport 'self-portrait'. |

|

|

In some

ways, Andrew says now, it will never be finished. "I

just keep finding Anno and discovering more about him every

day." If it had been another of his sons, he says, it

might have been harder to bear, because they wouldn't have

left all this creative archive behind. He sympathises deeply

with Alberto's mother, who only had about eight photos of

her son. Andrew, by contrast, has so many hours of film and

video footage of Anno and his brothers that it would take

him three months to watch it all, 24 hours a day, seven days

a week. He acknowledges that the awesome scope of technology

available to everybody has enabled all this archiving (he

has never, for example, so much as kept a diary himself).

The KjD website stands as the most extraordinarily moving

tribute to his son and the band, a kind of living gravestone.

But

now that it's kind of finished, and the CD is coming out,

and the poetry will be published, he can return to one of

his unfinished projects: J M Barrie. (He bequeathed all

his royalties from the TV film and the book to Great Ormond

Street Hospital but still has a wealth of research material,

which will be auctioned on behalf of the hospital next year

to buy incubators in Anno's memory). He has always felt

that his relationship with Barrie is not yet over. He's

got a producer, he's got a title, he's got a story and he

recently wrote the first ten pages. He's even got the beginnings

of a cast – he wouldn't consider anyone else but Ian

Holm for the role of JMB, and he recently met someone he

thought could play Michael. Anno, whom he once considered

for the role, always felt that his father shouldn't make

another Barrie film unless he had something new to say.

In his introduction to the reissued book, Andrew writes:

"I don't remember reading Peter Pan to Anno

or his brothers. I don't think he ever saw The Lost Boys,

or read the book. He didn't need to. Whether I make another

Barrie film remains to be seen, but yes Anno, I do have

something new to say."

* * * * *

Who Said The Race Is Over? by Anno Birkin - a selection

of poems with Introductions by Bruce Robinson and Ian Warwick - is published by Laurentic Wave Machine @£8, and is available through bookshops or via this link at Amazon.co.uk. All royalties go to Anno's Africa.

Dreams of Waking by Kicks joy Darkness, with a bonus

CD of Anno's earlier songs, is distributed by Cargo in the

UK and is available through record shops or via this direct link at Amazon.co.uk @ £12.99. All royalties go to Anno's Africa.

J M Barrie & the Lost Boys is published by Yale University

Press (reviews). Author's royalties donated to the Great Ormond Street Hospital. The website is at www.jmbarrie.co.uk.

The Lost Boys - Birkin's award-winning BBC trilogy - is available on DVD, both in the UK and USA. Author's royalties donated to the Great Ormond Street Hospital. (reviews).

View/download Sredni Vashtar (350k, 28 min)

Copyright

© 2003: Jessamy Calkin & the Telegraph Magazine.

|